geolocators: the background

Since 1909, the start of the Ringing Scheme, nearly 110,000 Spotted Flycatchers have been ringed in Great Britain and Ireland.

traditional metal-only ringing

Until the use of mist-nets became widespread in the 1950s and 60s, most Spotted Flycatchers were ringed as nestlings. This is still largely the case today; out of 1,164 flycatchers ringed in 2018 (down from an average 3000 in the 1980s), only about half were full-grown birds. 12% of this total (adults and nestlings) were ringed in Cambridgeshire, Flycatcher nests in and around human habitation, and particularly in nestboxes, are easy to monitor. All of this effort over all this time has produced only 141 ring-recoveries overseas. Most of these have been young birds shot or trapped in the mid/late 20th century en route to Africa via a south-westerly route during their first autumn (Spain 55, Portugal 20, France 19 and Morocco 19).

Evidence from the ring-recoveries of birds ringed in northern and eastern Europe has shown that there is a migratory divide, with flycatchers east of 12°E taking a route out of Europe through the Balkans and the Middle East, where they still face similar hunting pressures.

passage and wintering ring-recoveries

All that ringing effort has not been particularly helpful in determining the winter quarters of British flycatchers. There have only ever been eleven sub-Saharan ring-recoveries from Britain and Ireland – as shown below (Ghana 1, Nigeria 4, Congo 3, DRC 1, Angola 1, South Africa 1). The South African recovery looks very odd – it was a late passage juvenile caught on Bardsey on 30 August and ‘found dead after a storm’ in the Eastern Cape in March.

[African ring-recoveries sometimes tell us more about the distribution of hunters and trappers than they tell us about the birds…]

There is a detailed analysis with excellent maps of all pre-1975 ring-recoveries from across the whole of Europe in Gerhardt Zink’s European ring-recovery atlas

Red line: the ‘divide’ at 12°E .

Extending this out to all European countries, there were only about 60 trans-Saharan ring-recoveries (including the UK ones as above), chiefly in passage periods, recorded by the time The Birds of the Western Palaearctic was published in 1993. Eleven of these were in West Africa; most (35) in the Zaïre basin; one in Angola. Five recoveries in eastern South Africa comprised four from Finland (east of the ‘divide’) and the anomalous Bardsey bird above, which may of course have been a drift-migrant from Eastern Europe, and thus may not even have originated in Britain.

questions

If British flycatchers were declining as a result of higher mortality on passage; at stopover sites; or at their final wintering destinations, then traditional ring-recoveries have not been providing sufficient answers to our questions. We need to understand

- the timing and routing of migration

- the location, timing and duration of any stopovers

- the location of wintering areas

- winter site fidelity

- wintering ‘connectivity’

Flycatchers are obviously perceived as a ‘British’ bird and yet some may spend only two months of the year in the UK. Cuckoos (and male Cuckoos in particular) may spend even less time here – sometimes as little as six weeks. Both species must face all manner of risks and threats in the remaining months of the year as they cross Europe and the Sahara down into their winter quarters and return from them in the spring.

east vs west

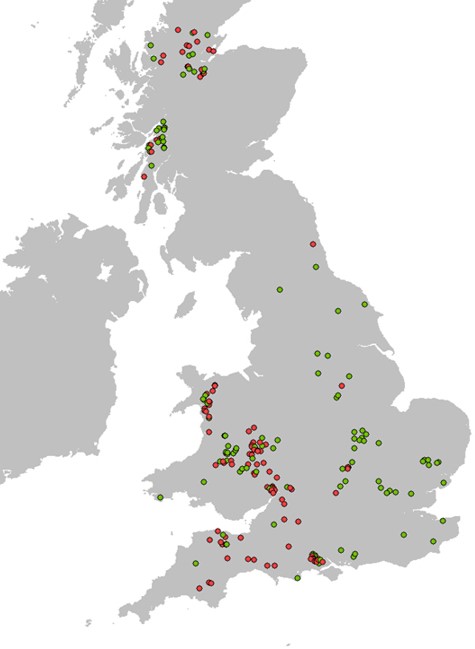

The Atlas-based analyses of the decline in abundance have raised the possibility that flycatchers were doing better – or at least declining less rapidly – in the north and west of Britain compared with the south and east. If true, this might be a function of conditions in the breeding season: changing climatic conditions (particularly rainfall); differences in farming (mixed vs arable, pesticide use); or differential rates of decline in large flying insect populations.

Or it could equally or additionally be due to a difference in migration and wintering strategies by discrete sub-populations.

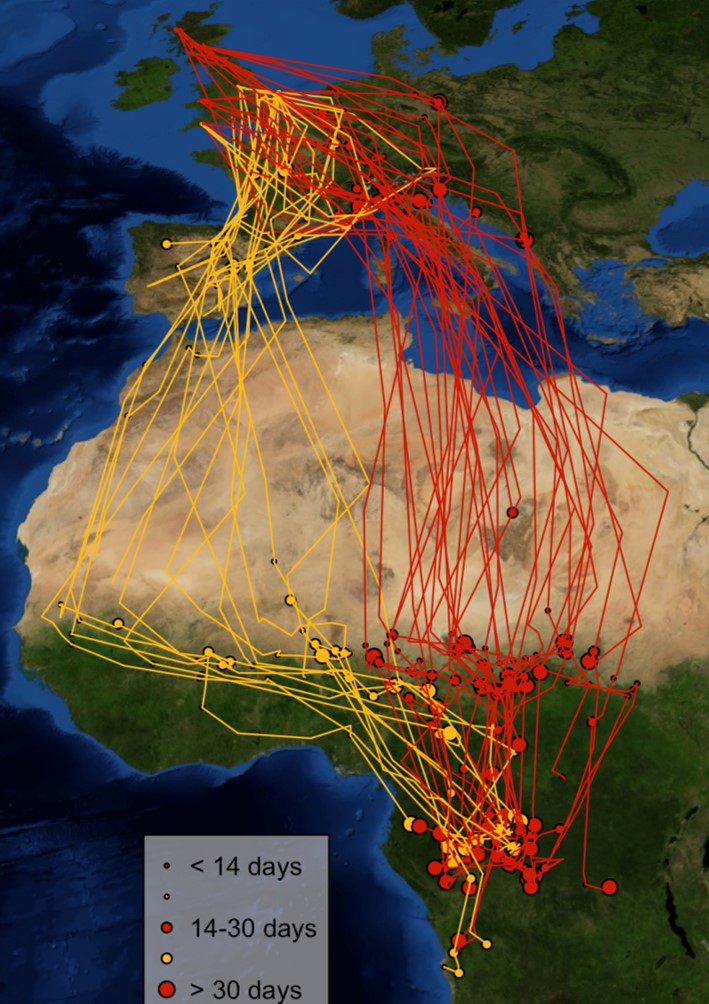

BTO Cuckoo research has shown that a migratory divide might be accounting for different rates of survival within two British sub-populations. Only 57% of adult British Cuckoos taking a western (Iberian) route in autumn managed a successful Saharan crossing. In contrast, 97% of those migrating via Italy and the Balkans did so. The proportion of birds taking the less successful ‘yellow route’ correlated with local population decline, suggesting a link. These birds suffered high mortality in south-western Europe, perhaps because drought conditions were preventing them from finding sufficient food.

Could something similar be happening with flycatchers?

In addition to the implied evidence in recent BTO Atlas maps, the BTO/RSPB Repeat Woodland Breeding Survey (1960–80) had also suggested this difference in the fortunes of northern/western as compared with southern/eastern Spotted Flycatchers.

An important research study The breeding biology of the Spotted Flycatcher in lowland England by Danaë K Stevens had two separate study areas, one in Devon, the other on the Bedfordshire Cambridgeshire border. This is probably the best current resource available on the species. Densities of flycatchers were twice as high in the Devon study area (2004–06 mean 1.8 pairs/km2) than in the Bedfordshire/ Cambridgeshire study area (2005–06 mean 0.9 pairs/km2). The eastern birds bred just as successfully as those out west, perhaps even more so, even though their population was declining. As part of this study, feather samples were analysed to measure the distribution of stable isotopic signatures. There were insufficient differences between signatures from the two study areas to suggest that the two populations were wintering in separate areas.

The early results from the geolocator project suggest that there may not be migratory differences between the Cambridgeshire and Devon birds. What is needed now are some geolocator tracks from birds from some of the other more successful populations – Scotland and Ireland.